Leviathan, the all-powerful sea monster of the Old Testament, was Thomas Hobbes’s metaphor for the state: “that Mortall God to which wee owe . . . our peace and defence.”1 Without Leviathan’s laws and coercive powers, Hobbes maintained, our lives would be “solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short.” By submitting to Leviathan, he argued, we make our lives free and open to the development of civilization.

Since Hobbes we have learned that there are many Leviathans, not all of them benign. A recent authoritative study of state building classifies them: Despotic Leviathan (the oppressive state), Absent Leviathan (the failed state), and Shackled Leviathan (a state restrained by its own laws and by an active civil society). There is also Paper Leviathan (despotic by intention, but mostly ineffective or absent).2

In this book I write about the state of the Soviet Union—a regime that was clearly despotic, with a remarkable coercive capacity. Unlike those forms of despotism that rely on informality, every action of the Soviet state left a winding paper trail of decrees, orders, correspondence, forms, reports, inquiries, investigations, and audits. But this was no ineffective Paper Leviathan, for the paperwork covered every aspect of Soviet life and the decrees and directives had profound impacts on the lives of every citizen.

The Soviet state existed for seventy-four years from the Bolshevik coup d’état of October 1917 to its collapse in December 1991. Those seven and a half decades place the Soviet Union among the most long-lived of modern dictatorships. While it existed, it was also among the most secretive of modern states. The disproportion between what went on behind the scenes and what was disclosed to the public was immense. When the state collapsed, its wealth of secret records was abruptly exposed to scholarly investigation. The records show in detail the deliberate building of a powerful authoritarian state and of its industrial and military power.

I call this state Secret Leviathan. Secrecy was in the genes of the Soviet state from the first days of its creation. The Soviet state took secrecy to an extreme. When secrecy failed, the state collapsed. This book is about Soviet secrecy and its consequences.

All governments of the early twentieth century kept secrets, from military and diplomatic secrets to the confidences that arose in the ordinary business of politics. The government of the Russian Empire before the Bolsheviks was no exception. It is what came next that was exceptional.

In its first days, the new regime did not hesitate to expose the secrets of the old regime such as the record of confidential inter-Ally negotiations on a postwar settlement.3 Regarding their own secrets, the Bolsheviks’ attitude was entirely different. They set about cloaking their activities and suppressing critical voices far more energetically than before. Their ability to do this was limited at first. It took time for the systems to be built that would enable to them to achieve their goals.

Soviet government was known for its unusual secretiveness during the Cold War. “The main characteristic of the Soviet government,” wrote the American journalist John Gunther, “distinguishing it from all other governments in the world, even other dictatorships, is the extreme emphasis on secrecy.”4 Western observers were aware that the Soviet state concealed many secrets, that there was comprehensive censorship of the press and media, and that most Soviet people were kept in the dark about nearly everything that went on outside their own narrow circles of acquaintance.5

Much remained unknown, however. When the Soviet Union collapsed and the archives were opened, aspects of Soviet secrecy emerged that were completely unexpected, even for the veteran scholars that found them. One surprising discovery was the sheer size of the Soviet Union’s secret sphere in comparison to the size of the public sphere. If what was published was the tip of an iceberg, how much lay beneath? Here, the economic historian R. W. Davies comments on the discovery that the volume of secret Soviet government business in the 1930s exceeded the business disclosed to the public by a whole order of magnitude:

Between 1930 and 1941, as many as 3,990 decrees of [the Soviet central government] and its main economic committee were published. We naively thought that this included a high proportion of the total. We now know that the total number of decrees issued in these years was 32,415. Most of these were “for official use only,” and over 5,000 were “top secret” . . . and were available only to a handful of top officials.6

Another surprise was the discovery of a formal code of secretive behavior to which all party members and state officials were bound to conform: “conspirativeness” (konspiratsiia). Here the social historian Sheila Fitzpatrick describes her first encounter. In September 1990 she visited the archive of Sverdlovsk (now Ekaterinburg), a previously “closed” provincial capital. There she came across an instruction of the early 1930s on the classification and handling of paperwork:

A sentence jumps out about rules for handling “correspondence of Party organs and other conspiratorial documents.” Conspiratorial documents? When this is a ruling party, in power already for fifteen years? . . . [The archive director] comes in; I ask what he makes of “conspiratorial documents” phrase about party correspondence. New to him.7

A third surprise was the extreme compartmentalization of Soviet secrecy. All bureaucracies are divided into compartments, and it is of the nature of these divisions that they impede cooperation and communication. But in the Soviet bureaucracies the walls between government departments were as high and as impenetrable as those that shielded the state from the public. I recall my wonder at the documentation of a dispute between the Soviet Interior Ministry (MVD) and the Finance Ministry in August 1948. The Finance Ministry was preparing the national budget, which included payments toward the upkeep of the millions of detainees and guards in the labor camps of the MVD. The budget officials asked the MVD officials to confirm the numbers. The MVD refused: “Provision of these figures will lead to familiarization with especially important information on the part of a wide circle of staff of the USSR Ministry of Finance, the State Bank, and the Industrial Bank.” (“Especially important” was the highest secrecy classification.) The MVD advised Lavrentii Beria, Stalin’s deputy, that in past years such figures had been loaned temporarily to the Finance Ministry to be processed by no more than two or three highly trusted workers, then returned. It noted that the ministries of the armed forces and state security provided the Finance Ministry only with financial summaries, not head counts; and it proposed that from now on the MVD should do the same.8

Since those early finds, there have been two kinds of further revelations. On one side, the Soviet archives have yielded many specific secrets. Studies and documentary collections have been published that show the secret working arrangements of the top party leaders and of secret branches of activity such as the secret police, the armed forces, the defense industry, the closed cities of the military-industrial complex, and the Gulag system of forced labor camps.9

On the other side were revelations that laid bare particular aspects of the organization of secrecy. These included accounts of the secret archives themselves; the rules pertaining to what was secret and what was not; the development of the censorship; the concealment of people, objects, organizations, and entire cities; the formalization of “conspirative” decision making; the parallel evolution of government communications on paper and by telephone; and the operation of secret processes such as the vetting of personnel for access to secret information.10

After all this, there remains the task of understanding the system as a whole: how the parts fitted together to constitute a system and what were its consequences. The system had a name, but even the name was secret, being unknown to the public until Soviet secrecy collapsed. The “regime of secrecy,” as insiders named it, is defined here for KGB officer trainees of the 1970s in a secret handbook copied and made available for scholars during the 1990s:

REGIME OF SECRECY: the totality of rules determined by the organs of power and administration that limit the access of persons to secret documents and activities, codify the procedure for use of secret documents, correspondingly regulate the conduct of people involved with secrets, and provide for other measures.11

The Soviet regime of secrecy was not unchanging. As described in this book, it was formed by beliefs and interests in an atmosphere of conflict and mobilization. It evolved by trial and error over many years. Throughout the process, a few fundamentals can be observed. Not all were there at the beginning but, once in place, they persisted to the end.

The Soviet regime of secrecy was built on four pillars that gave it exceptional coverage and iron grip. These pillars were the state monopoly of nearly everything, the censorship of the press and media, the conspirative norms of the ruling party, and the secret police and secret departments. I will briefly describe each in turn.

The state monopoly of nearly everything was the first pillar of the regime of secrecy. Under the Soviet command system, production, distribution, trade, transport, and construction were carried out almost entirely under state ownership and control. The private sector was relegated to the margins of agriculture, handicrafts, trade, and personal services. As a result, most matters that would have been private business in other countries became the business of the government. At the same time, all government business was politicized, in the sense that the ruling Communist Party based its decisions on political criteria that could override any economic, cultural, and technical considerations. In the outcome, the political business of the Soviet state was far more completely encompassing than the business of other states, including the Russian Empire that came before it.

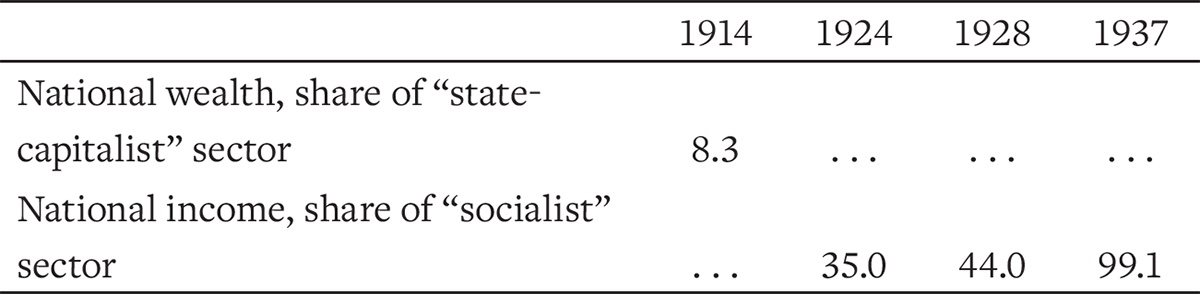

The historical process that brought this about is suggested very approximately by Table 1.1. This table reports the share of the state-owned sector in the economy in benchmark years from 1914 through 1937. The first figure shown, 8.3 percent, gives the share of the “state-capitalist” sector in the reproducible assets of the Russian Empire. Before the Revolution, therefore, private capital was heavily predominant. Later figures are shares of the “socialist” (i.e., state and cooperative) sector in the Soviet Union’s net material product. Shares of output are not exactly comparable with shares of capital, but they are sufficiently so for a broad-brush comparison.

If the state’s share of Russian economic activity was small in 1914, the 1920s are often counted as a period of a “mixed” economy. In 1924 the socialist share in the Soviet economy is reported as one-third, and nearly one-half in 1928. The increase in state ownership in 1928 over 1914 is accounted for by the nationalization of land, large-scale industry, and finance. After that, the share of the socialist sector jumped again and became almost complete. The state-owned sector received nearly all new investment funds and grew rapidly. Private industry, trade, and services were starved and repressed. Most agriculture was nationalized or “collectivized,” and collective farms fell largely under state control, although their assets other than land were nominally the joint property of the farmers. The size of the socialist sector in 1937, reported as 99 percent, is somewhat exaggerated by including as “socialist” the peasants’ private sideline farming of public land allotted to them by the collective farms from 1932 onward. Still, despite the scope for mismeasurement and overstatement, the trend is unmistakable. By the 1920s, state ownership was already much more prevalent than before the Revolution, and it became almost universal in the 1930s.

As the Soviet economic system emerged, the Soviet state acquired a near monopoly of productive capital. Along with this came the potential to monopolize the supply of an unusually wide array of information. Information is the result of activity. If the state controlled most activities, it could also control the information that they produced. In particular, state ownership was extended to publishing and the media. In short, the state monopolized the economy, which gave it control over information across an abnormally wide range, and over the channels by which information could be disseminated to the public—or blocked.

The Soviet state used its monopoly of nearly everything not only to control public information but also to suppress private information sharing. One technology that was deliberately restricted was the photocopier. A Soviet photocopier was designed in the early 1950s by the electrical engineer Vladimir Fridkin. But it posed a threat to the Soviet state’s monopoly of printed matter. In the Institute of Crystallography, where Fridkin worked, colleagues often asked him to copy articles from foreign journals, bypassing the official channels. Once this came to their notice, the KGB ordered the machine to be dismantled and its development was halted.12 Denied access to photocopying, dissidents who wanted to self-publish manuscripts (so-called samizdat) had to rely on carbon copies laboriously typed or retyped at home; carbon paper could not make more than three or four legible copies at a time.

Another restricted information technology was dial-up telephony. The convenience of local dial-up phone networks was too great to be dispensed with (although consumer access was impeded by stopping publication of household telephone directories after the 1920s). But the Soviet authorities delayed public access to long-distance dialing by many decades. To phone a friend in most other towns required the help of a switchboard operator at the local exchange. International calls had to be booked hours or days ahead. During the 1960s, a few larger cities were connected to Moscow by intercity dialing. By 1971, when the coverage of long-distance dialing in the United States was almost complete, nearly two-thirds of Soviet long-distance calls were still connected by a human operator. One result was to restrict the private channels through which information could flow over any distance: the average Soviet person made fewer than 2 long-distance calls in 1970 compared with 35 calls in the United States and as many as 99 in Sweden, a much smaller country.13 The effect was to limit long-distance and international calls to the eavesdropping capacity of the KGB.14

The Soviet government escaped the main burden of the restrictions that fell on private households and the civilian population. Imported photocopying machines could be licensed to government offices, subject to the availability of scarce foreign currency (another state monopoly).15 As for automated dialing, as early as 1922 Lenin’s government bought and installed the so-called vertushka, a dial-up phone network that linked the top Kremlin leaders, bypassing the ears of the switchboard operator. Within a few years, high-frequency automated phone systems connected ministries and regional party offices to the center over long distances.16

The state monopoly of nearly everything was the first pillar that held up the regime of secrecy. While holding a monopoly inevitably creates temptations, however, it does not predetermine exactly how the monopoly will be exercised. In the Soviet Union, that depended on the other pillars that were put up at the same time.

Comprehensive censorship of the media and publishing was the second pillar of the regime of secrecy. The Bolsheviks took their first step to new rules for publishing and the media as early as 9 November 1917, two days after their coup d’état. The Decree on the Press was a preventive measure, intended to smother the newspapers opposed to the Bolshevik Revolution. The new Council of People’s Commissars gave itself powers to close publications that advocated its overthrow, or disseminated fake news, or incited criminal acts. The rationale given was that freedom of the press was merely freedom for the propertied class that owned the presses. The powers taken were temporary—to be rescinded upon the return of “normal” conditions.17

At this time the new measure was not particularly effective: while the state did not own all printing presses, it was a simple matter for a newspaper banned under one title to reappear under another. But, whether effective or not, the restrictions were never repealed. In the late summer of 1921, the political emergency eased. The Civil War was over, and the harvest had not yet failed. There were calls to restore press freedom. Instead, Lenin dug in his heels; he denounced the idea of media liberalization as “suicidal,” giving the same reasons as in 1917 despite the better situation.18

In 1918, the restriction of the opposition press was followed by measures to limit the scope of information that it was permissible to publish. No one authority was put in charge, so a division of responsibility emerged: the Cheka (as the Soviet secret police was first called) looked after political secrets while the Revolutionary Military Council did the same for military secrets. Cable traffic from abroad was monitored by the Foreign Ministry. The Ministry of Enlightenment took care of the state publishing house (schools and literature).19

While these measures certainly had a restrictive effect, they were only first steps on a long path to the comprehensive, centralized censorship of later years. The next important measure was the establishment of an office of the censor, known as Glavlit, on 6 June 1922. (Its full name, the Chief Administration for Literature and the Press, went through many variations, but the short form was retained to the end.) The first list of prohibited topics was promulgated: anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda, military secrets, false information causing alarm, information inciting ethnic and religious hatred, and pornography.20 But the system was not watertight because censorship remained decentralized and was implemented with many inconsistencies and loopholes.

By 1930 or so, the wrinkles were ironed out and the leaks were stopped.21 From that time, the censors ensured that scarcely a word was printed or broadcast from one end of the Soviet Union to the other without prior scrutiny. They kept from circulation the least hint that could reflect badly on the ruling party or its leaders.

Comprehensive censorship, the second pillar of the Soviet regime of secrecy, was exceptionally effective. Throughout the history of the Soviet state there were few leaks. Great facts that were effectively concealed include the famines of 1933 and 1947, the mass killings of 1937 and 1938, Soviet responsibility for the Katyn forest massacre of 1940 (the event itself was uncovered only by the accident of Germany’s wartime occupation of the territory on which it took place), the scale of forced labor, the military and population losses of World War II, the burden of Cold War military outlays, and the exact geolocation of almost everything, including the existence of some cities.

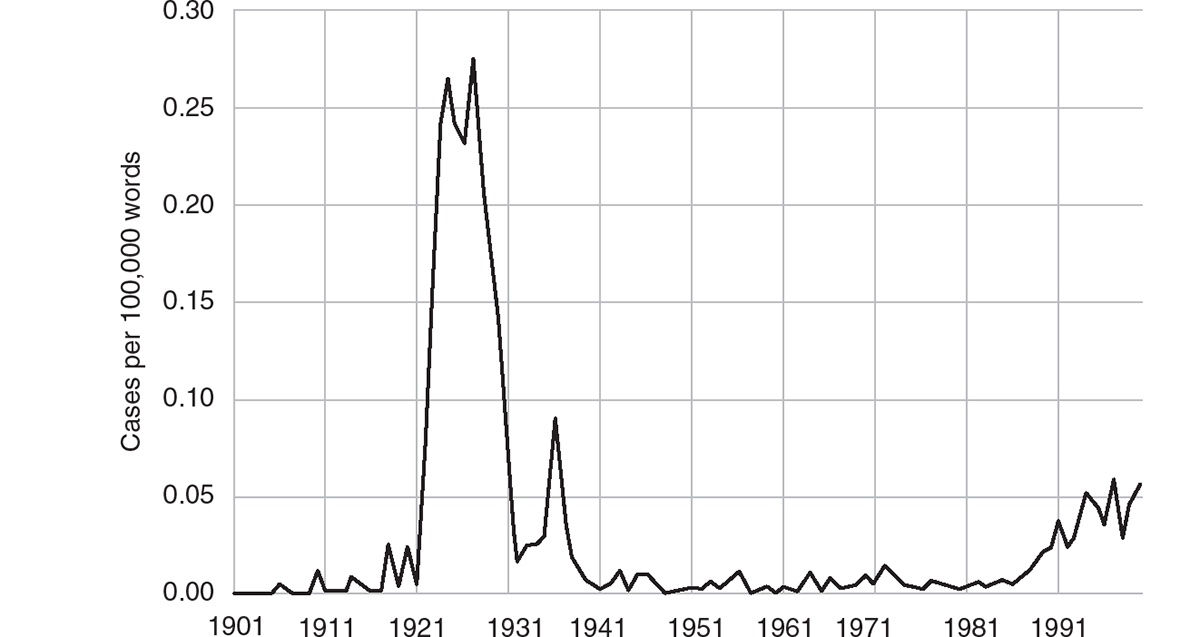

A simple yet unambiguous measure of the effectiveness of the censorship is shown in Figure 1.1. How well did Glavlit suppress discussion of its own existence? The Google Books Russian-language corpus of 2019 gives access to the digitized texts of 600,000 books published in the twentieth century. The vertical axis shows the frequency of mentions of “Glavlit” per 100,000 words per year; this was close to the average length of a book in the corpus. The data start in 1901, when Glavlit did not exist. In each year before 1922, when Glavlit was established, the probability of finding a single mention of Glavlit in a published book was zero or, if not zero, so close to zero as to be explained, most likely, by a typographical error or an error of digitization. In the years from 1922 to 1930, the censorship was being built, and Glavlit was mentioned and discussed in public, so the probability of finding a mention of “Glavlit” in a book of average size soared, peaking at around one-quarter. Of course, a single mention is not a discussion, so the probability of finding a discussion of Glavlit might be one or two orders of magnitude less. But in 1931 the frequency fell back to zero, or close to zero. The hush that followed was disturbed only by an occasional murmur (in 1936, for example, the frequency briefly returned to one-tenth before falling back). After that, from the late 1930s to the late 1980s, that is, for a full half century, silence reigned.

Only after Gorbachev initiated the policy of “openness” (glasnost’) in 1987 did uncensored discussion of Glavlit resume. It never returned to the level of the 1920s, for public interest was now limited to the narrow circle of historical scholars. Anyway, the lesson is that Soviet censorship worked.

What was permitted by the Soviet censors varied over time, although generally within strict limits. Writing in the first half of 1953, the economist Abram Bergson offered a simple gauge of the tendency of the secret sphere to encroach on what was previously disclosed. He used the quantity of published documentation of successive Soviet five-year plans for the national economy.22 The first five-year plan (1929) amounted to four published volumes, full of detailed economic and social statistics (although already with notable gaps and half truths). That quantity was halved for the second plan (two volumes in 1933) and halved again for the third (one volume in 1938). The third was the last plan to be published before war broke out. The postwar period saw further restriction. The fourth plan (1946) was published in six newsprint pages in Pravda, with the fifth plan (1950) covered in just three pages.

After Stalin’s death, the policy of increasing restriction was reversed. During the post-Stalin “Thaw” (discussed below) the censors allowed a return to regular publication of economic and social statistics. Although the data published were heavily selected and the gaps remained notable, the change in policy was large enough to have important effects on the atmosphere and substance of the Soviet Union’s public discourse. Thus, a policy was changed, while the system remained the same. The strongest evidence of continuity is that, as shown in Table 1.2, the existence of the office of censorship was strictly shielded from public exposure.

The Bolsheviks did not invent censorship, which was practiced in Imperial Russia before the Soviet period. If there was continuity within the Soviet period, was there continuity from pre-Soviet times? The two systems cannot be evaluated in exactly comparable terms. The work of the historian Benjamin Rigberg makes possible only a rough comparison. He finds that the prerevolutionary statute on censorship seemed to give the imperial government sweeping powers to control the press and prevent publications that might disseminate critical views or subvert public order. But these powers remained largely unused for lack of resources. In 1882, forty-four censors were employed across the Russian Empire. By 1917, after thirty-five years of growth of the print media and in the middle of a world war, the number had risen to just forty-six. While the censors’ efforts were not completely ineffective, they did little to intimidate a lively public sphere where great issues were debated in a spirit that was often hostile to authority.23 Rigberg concludes:

It is now clear that the tsarist regime made improper provision for the attainment of its aims. Even a staff twenty or thirty times larger than that actually functioning could scarcely have supervised effectively the vast printing operations of tsarist times. It thus seems obvious that the government cannot itself have attached overriding importance to censorship operations; else why so paltry a budget for the Chief Administration? However one speculates the conclusion seems inescapable: Censorship was not a major arm of repression which the Old Regime relied upon.24

In the 1960s, by contrast, the staff of Glavlit numbered not 46, nor even twenty or thirty times 46, but at least 70,000 according to a contemporary estimate.25 A preliminary conclusion is therefore that the imperial censorship was far from comprehensive: it was a pale shadow of its successor, and no more.

The conspirative norms of the ruling party were the third pillar of the regime of secrecy. The Soviet state was brought into existence by a conspiracy, and it continued to be organized as a conspiracy until it passed from the scene. The third pillar of the regime of secrecy was the code of conspiratorial practices that each Bolshevik generation learned from those that came before and passed on to those that followed. These norms freed members of the party in power from any sense of obligation to account in public for the decisions they made or for their outcomes. On the contrary, the greatest obligation that they felt was to each other. This was expressed in the code of silence that they called konspiratsiia: “conspirativeness.”26

What were “conspirative norms,” exactly? When Soviet leaders and officials talked about them, they seem to have meant three things. First was the principle of need-to-know. In the words of a Politburo resolution “On the Utilization of Secret Documents” (dated 5 May 1927), “secret matters should be disclosed only to those for whom it is absolutely necessary to be informed.” The extreme compartmentalization of information was a direct result.

The second norm was personal accountability. The security of every chain of secret correspondence would eventually be assured by recording every document and registering it to an individual sender, courier, receiver, or keeper at every stage from creation to destruction or to the archive. The regulations that set out personal accountability and the records that assured it would also be secret and subject to the same rules.

The third conspirative norm was exclusiveness. No one should be admitted to secret correspondence whose reliability was not assured by prior vetting and approval. The channels of secret correspondence should themselves be secret and kept strictly separate from open channels such as the public postal and telephone services.

The code was there from the start but, just as with other aspects of the regime of secrecy, its formalization took time. The historian of party secrecy Gennadii Kurenkov notes the lack of a paper trail leading back to the original source of the secretive practices of the party in power. What is visible is that a “special” department of the party secretariat had been established within eighteen months of the Bolshevik Revolution (by March 1919), and a “conspirative” department existed already in 1920.27

At first, while the Bolshevik leaders could talk about conspirativeness all they wanted, paper records were not secure and presented great risks. For this reason, Lenin’s private messages of the period were peppered with demands for the recipient to take extreme precautions—to treat the contents “arch-conspiratively” or “arch-secretly.”28 For the same reason, some early decisions of the party in power were not committed to paper, or the records were destroyed. An example is the lack of a paper trail accounting for the decision to execute Tsar Nicholas II with his family and retainers in Ekaterinburg on the night of 16 July 1918.29 As record keeping became more secure, however, the need for informality diminished. Twenty years later, much greater crimes were committed to paper in excruciating detail.

While the Civil War continued, few discernible efforts were made to codify and elaborate the rules of secrecy. During 1918–1920, leading party committees discussed such matters no more than a handful of times. The situation changed from 1921, when the party secretariat (and, from 1922, Stalin’s Orgburo) began to consider communication security on average around twice a month.30

The rules of secret correspondence were formalized in a series of Politburo decisions, the first being a resolution of 13 August 1922, “On the procedure for storage and transmission of secret documents.”1 After that, nearly every year brought new or updated regulations such as the “Rules on handling the conspirative documents of the Central Committee” (19 August 1924) or “On conspirativeness” (16 May 1929). On each occasion the rules became more specific and binding, often in response to violations or the discovery of grey areas.32 This process would continue for decades, but the principles remained unchanged and were evident from the outset.

The historian Larissa Zakharova has described the parallel emergence of the conspirative phone call.33 Written communication among the top leaders over any distance, whether of one kilometer or thousands, risked loss or interception. At first the telegraph and dial-up telephone seemed to offer a way to reduce or even eliminate the risks. The parallel rise of signals intelligence frustrated these hopes. Secure telecommunications required protection by coding or scrambling. In turn, this brought in third-party experts, who had to be vetted for loyalty and monitored. In the process, the Soviet secret police developed a substantial capacity for eavesdropping and phone tapping.

In short, conspirative norms were the special contribution of the Bolshevik party to Soviet secrecy. It is important to bear in mind, however, that conspirative norms could not have had their influence without Bolshevik control of the state, or without state control of the means of production, information, and publication.

The secret police and the secret departments were the fourth pillar of the regime of secrecy. Because government secrecy was identified with the security of the state, the procedures of secrecy were overseen by the same secret police that defended the ruling party by suppressing criticism and opposition. This was the Cheka (the All-Russian Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counterrevolution and Sabotage), renamed the GPU (Chief Political Administration) and OGPU (Unified Chief Political Administration), the functions of which were eventually absorbed by the NKVD (People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs), then devolved upon the NKGB (People’s Commissariat of State Security), renamed MGB (Ministry of State Security) after World War II, and reformed after Stalin’s death as the KGB (Committee of State Security).34

The secret police exercised its oversight of all other branches of the state by a distinctive innovation. This was the institution of the “secret department” (renamed the “first department” in 1965). From 1922, every state enterprise, office, institute, and facility of any kind and size across the Soviet Union maintained a secret department responsible for government communications and documentation, staffed by party members and regulated by the secret police.35 In this way the entire state was brought into alignment with the party in its conspirative channeling and secure storage of information.

As supervisor of the secret departments throughout the government apparatus, the KGB was charged with ensuring that secret papers were safely stored and transmitted, vetting the employees whose jobs required access to secret communications, scanning the workforce for security risks, and investigating violations.

A related innovation enabled many government facilities to disappear from the public view: the numbering of key installations. On its nationalization in 1918, the former Duks aircraft works was renamed State Aviation Factory no. 1. Some motor factories were also renamed and numbered at around the same time. At the time this was primarily symbolic. In practice, the factories were often still referred to under their former names. In 1927 the defense sector of the economy began to be withdrawn into the secret sphere, and numbering proved to be a useful way to anonymize them. The first centralized list of fifty-six defense plants was drawn up and some of them were renumbered. At the same time, war-mobilization departments were set up in every supply ministry and every province.36 Eventually labor camps were also brought under the same level of security as defense installations (as discussed in Chapter 4).

For a while there were many inconsistencies and overlaps, and new and old factory numbers were used interchangeably. These were an impediment to concealment because some facilities then required additional identifiers to avoid confusion. While some anomalies were never ironed out, the lists of numbered factories became more and more extensive and all details of their former names, locations, and production profiles disappeared from the media, only the numbers themselves being mentioned on rare occasions. Over many years the British defense economist Julian Cooper based his personal register of numbered factories on Soviet press reports of the award of honors and decorations, for example, that the director of factory no. such-and-such had been named a Hero of Socialist Labor.

1. The Bible, Job 41; Hobbes, Leviathan.

2. Acemoglu and Robinson, The Narrow Corridor.

3. Carr, Bolshevik Revolution, book 3, 24–25.

4. Gunther, Inside Russia Today, 537.

5. Some who wrote knowledgeably during the Cold War about what they could see of Soviet secrecy from the outside were journalists (Gunther, Inside Russia Today, 74–81; Smith, The Russians, 420–57); some were specialists (Bergson, “Reliability and Usability”; Hardt, statement in US Congress Joint Economic Committee, Allocation of Resources in the Soviet Union and China; Hutchings, Soviet Secrecy; Maggs, Nonmilitary Secrecy; Rosenfeldt, Knowledge and Power and Stalin’s Special Departments). Among the contributors were also Russian insiders who made it to the West while the Cold War was still on (Vladimirov, “Glavlit”; Zhores Medvedev, Medvedev Papers and Soviet Science; Birman, Secret Incomes; Dunskaya, Security Practices at Soviet Research Facilities; Agursky and Adomeit, “The Soviet Military-Industrial Complex”).

6. Davies, “Making Economic Policy,” 63.

7. Fitzpatrick, “Closed City and Its Secret Archives,” 780.

8. Harrison, “Economic Information,” 99. A handwritten note on the MVD proposal reads: “Comrades Popov and Serov: consider and resolve. L. Beria.”

9. Among the first collections of this nature were Gregory (ed), Behind the Façade of Stalin’s Command Economy, and Gregory and Lazarev (eds), Economics of Forced Labor. The literature concerned, too voluminous to itemize here, has been surveyed by Gregory and Harrison, “Allocation under Dictatorship”; Kuromiya, “Stalin and His Era”; Ellman, “Political Economy of Stalinism”; Kragh, “The Soviet Enterprise”; and Markevich, “Economics and the Establishment of Stalinism.”

10. Secret archives: Khorkhordina, “Khraniteli sekretnykh dokumentov.” What was secret and what was not: Bone, “Soviet Controls on the Circulation of Information.” The censorship: Goriaeva, Politicheskaia tsenzura; Kurenkov, Zashchita voennoi i gosudarstvennoi tainy. Concealment: Siddiqi, “Soviet Secrecy” and “Atomized Urbanism”; Jenks, “Securitization and Secrecy.” Conspirativeness: Khlevniuk et al., eds, Stalinskoe Politbiuro; Kurenkov, Ot konspiratsiia k sekretnosti; Rosenfeldt, “Special” World. Government mail and telephone communications: Zakharova, “Trust in Bureaucracy and Technology.” Vetting personnel: Grybkauskas, “The Soviet Dopusk System.”

11. Nikitchenko et al., Kontrrazvedyvatel’nyi slovar’ (classified “top secret”), 279. The Google Ngram Viewer at https://books. google.com/ngrams (accessed December 8, 2020), described by Michel et al., “Quantitative Analysis of Culture,” shows that “rezhim sekretnosti” (the regime of secrecy) was effectively unknown in the Russian-language Google Books corpus of 2019 until 1987. The only exception is a tiny, near-imperceptible spike in 1956.

12. Churilov, “Pervyi sovetskii ‘kseroks.’”

13. Lewis, “Communications Output in the USSR,” 411–12.

14. On KGB phone tapping, see Harrison, One Day We Will Live without Fear, 195–200.

15. At times the Kremlin’s foreign exchange was so short that even a Republican KGB could be refused. On 18 March 1974, the chief of the Soviet Lithuania KGB wrote to Moscow on behalf of its information and analysis division requesting provision of a Xerox 720 photocopier. The refusal, dated 28 March, was based on “the extremely limited allocation of foreign currency.” Hoover/LYA, K-1/3/798, 26–27

16. Zakharova, “Trust in Bureaucracy and Technology,” 566–69. More generally, see Solnick, “Revolution, Reform and the Soviet Telephone System,” and Campbell, Soviet Telecommunications System.

17. For the English translation see under “Seventeen Moments of Soviet History,” http://soviethistory.msu.edu/ 1917-2/organs-of-the-press/organs-of-the-press-texts/ decree-on-the-press/. Egorov and Sonin, “Political Economics of Non-democracy,” maintain that propaganda and censorship are conceptually the same, in the sense that they both amount to the manipulation of information by truncating some true signal. Organizationally, however, propaganda and censorship place very different demands on state capacity, and this difference explains the emphasis of the present chapter.

18. Lenin, “Pis’mo G. Miasnikovu” (5 August 1921).

19. Kurenkov, Ot konspiratsii k sekretnosti, 169.

20. Kurenkov, Ot konspiratsii k sekretnosti, 170.

21. The centralization of the censorship is described by Goriaeva, Politicheskaia tsenzura, 162–240. The relative liberalism of the 1920s allowed E. H. Carr to take the story of his multivolume History of Soviet Russia through the end of 1928. Beyond that point, Carr decided, the growing secrecy of Soviet politics and policymaking became too great a barrier to the writing of history. Carr, Bolshevik Revolution, Book 1, 6, and Carr, “Russian Revolution and the West,” 27.

22. Bergson, “Reliability and Usability of Soviet Statistics,” 14.

23. Rigberg, “Tsarist Press Law”; “Efficacy of Tsarist Censorship Operations,” and “Tsarist Censorship Performance.” In 1906, for example, the scope of budgetary secrecy was debated in print as Russia moved toward constitutional rule. Avinov, “Sekretnye kredity v nashem gosudarstvennom biudzhete.” Avinov was a prominent Cadet (Constitutional Democrat). I thank Vasilii Zatsepin for this reference.

24. Rigberg, “Efficacy of Tsarist Censorship Operations,” 343.

25. Vladimirov, “Glavlit,” 41. The author, a Soviet science journalist, defected to the United Kingdom in 1966.

26. Various translations of konspiratsiia are possible. Rosenfeldt, “Special” World, 66, prefers the literal equivalent: conspiracy. This does not seem right: while the two words look the same, the Russian konspiratsiia suggests the essence of conspiracy rather than a particular plot, for which the Russian word would be zagovor. Katherine Verdery, Secrets and Truths, location 560, translates the Romanian conspirativitate as “conspirativity”; she identifies it with the compartmentalization of intelligence work. It is amusing to add that a book on KGB espionage in the United States (Haynes et al., Spies, chapter 4, under “Harold Glasser”) translates konspiratsiia as “tradecraft.” In its context, this makes perfect sense: conspirativeness was the tradecraft of spies. The distinctive feature of the Soviet Union is that conspirativeness was the tradecraft of every branch of government, including those concerned with, say, licensing motor vehicles, or fixing the price of admission to movie theaters. Finally, while Lih, “Lenin and Bolshevism,” 58, does not offer a translation, he emphasizes the original meaning of konspiratsiia, that of secure communication between the underground party and its agents in the mass movement.

27. Kurenkov, Ot konspiratsii k sekretnosti, 24, 46.

28. Voronov, “‘Arkhisekretno, shifrom!’”

29. Service, Last of the Tsars, 252–53. On Lenin’s efforts to avoid leaving written evidence of his involvement in various matters, see also 245–46.

30. Kurenkov, Ot konspiratsiia k sekretnosti, 102.

31. Kurenkov, Ot konspiratsiia k sekretnosti, 84.

32. Istochnik, “Praviashchaia partiia”; Khlevniuk et al., eds, Stalinskoe Politbiuro v 30-e gody, 74–77; Kurenkov, Ot konspiratsiia k sekretnosti, 224–45.

33. Zakharova, “Trust in Bureaucracy and Technology.”

34. Fainsod, How Russia Is Ruled, 425–27, recounts the establishment of the Cheka. Werth, “Soviet Union,” tells the history of the Soviet secret police up to the end of World War II.

35. Lezina, “Soviet State Security and the Regime of Secrecy,” 41; see also Rosenfeldt, “Special” World, 98–99.

36. Simonov, “‘Strengthen the Defence of the Land of the Soviets’,” 1360. Also, Cooper, introduction to Cooper, Dexter, and Harrison, “The Numbered Factories and Other Establishments.”